Historic Sutton Bridge – The Gateway To Lincolnshire

This ‘Our Town’ slot features different buildings and landmarks of local interest, some of them being ‘listed’, with a brief word about their historical interest. We would welcome any further information from the residents of Sutton Bridge, particularly if there are interesting stories to tell about them.

Known as the ‘Gateway to Lincolnshire‘, Sutton Bridge is a village and civil parish with a population of approximately 4000 inhabitants, situated in the South Holland district of south-eastern Lincolnshire and located on the west bank of the River Nene, close to the county borders with Norfolk and Cambridgeshire.

According to PREL (Peterborough Renewable Engergy Ltd), in their Screening and Scoping Opinion (Sept 2009), Sutton Bridge has no ‘scheduled monuments’ within 2km of their proposed development (4.4.5 (h) Page 17). Yet our town has eight listed buildings!

PARK HOUSE

Park House, formerly Metalair, now offices, is an early 19th Century Grade 2 listed building built in yellow brick but now has a C20 concrete tile roof. The open porch has free standing fluted columns (Doric) at the front and plain pilasters behind. The door is partly glazed and has single glazed sash windows on either side.

The house was built by the Guy’s Hospital Estate and was intended for their resident steward. Until 1919 Guy’s Hospital owned most of Sutton Bridge. The village had developed on part of their land and the Estate also built the church and the schools.

For further information about this and the industrial history of Sutton Bridge, please see the recently published latest edition of Sutton Bridge – An Industrial History by Neil Wright with help from Beryl Jackson. It is published by the Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology, Jews’ Court, Steep Hill, Lincoln, LN2 1LS and can be obtained from them price £11.95 incl. postage.

Two unusual listed buildings in Sutton Bridge

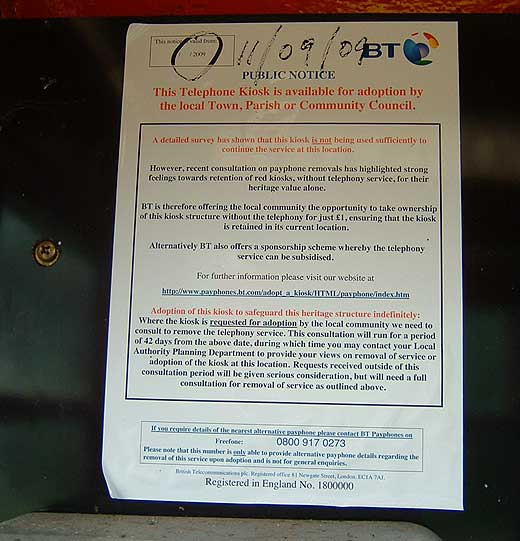

Red Telephone Kiosk, East Bank, Sutton Bridge

A Type K6 telephone kiosk, designed in 1935 by Sir Giles Gilbert Scott and subsequently made by various contractors. Made in cast iron, it is a square kiosk and has a domed roof. This is the most well known of all red telephone kiosks. Its red colour was chosen so that it would be highly visible, especially in an emergency.

In the 1990’s, BT replaced many of these traditional boxes with a more modern design. This led to a public outcry. In some places the red kiosks have been replaced, or disappeared. The telephone kiosk is still operational and maintained by BT.

In other villages, communities have adopted their kiosk and renovated it. This has happened in Foul Anchor. The telephone kiosk has a Grade II listing.

Milestone, Long Sutton Road

Constructed in the mid 19th century, the milestone is painted ashlar (which means a block of hewn stone with straight edges). It is rectangular in shape and 0.75m tall with a moulded front, on which is inscribed: ‘Spalding…’ but the rest of the inscription is illegible. On the right-hand side it reads: ‘Sutton Bridge 1 mile’ and ‘Long Sutton 2 miles’, although this is not as clear now as it was when it was first listed.

As can be seen from the two photographs, the milestone is no longer in an upright position and cannot be seen from the road. In order to take the photographs, we had to cut back the grass and nettles in order to be able to read the inscriptions.

While the milestone shown below is not the one mentioned in this article, it is in the centre of the parish of Sutton Bridge

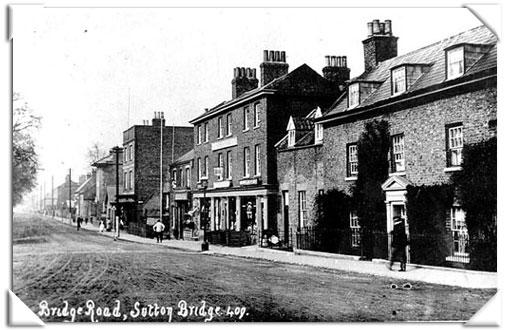

No. 2 BRIDGE ROAD

No 2 Bridge Road (now nos. 8 & 10), which is an early 19th Century red brick dwelling with a plain tile roof.

[Photo taken c. 1900]

Its imposing red front door makes it easily identifiable just across from the Green. The doorcase is topped with an open pediment. The door has an over light and on either side were single glazing bar sashes It has two storeys plus an attic with three bays, each with a single plain casement window. Today the building has been converted into six flats.

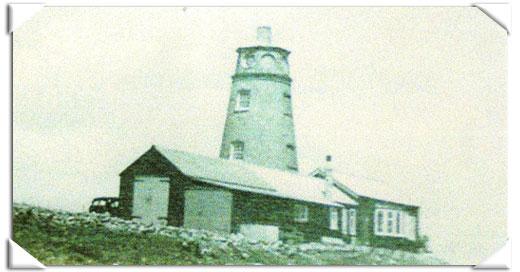

THE EAST & WEST BANK LIGHTHOUSES

The East and the West Bank Lighthouses in Sutton Bridge are both Grade II listed buildings. Both are described as early 19th century structures with 20th century alterations. Both are brick built, and have been rendered and colour washed. They each consist of a single central red brick stack of three storeys under a rounded lead roof plus an octagonal lantern.

The early history of the Lighthouses (before Sir Peter Scott’s time)

For a long time Sutton Bridge was part of the parish of Long Sutton. Today Sutton Bridge is officially a town even though the locals still think of it as ‘the Village’. It stands on land reclaimed from the estuary of the River Nene which flows into the Wash.

Since the Middle Ages land has been reclaimed from the Wash and the Nene estuary. Sea banks were built to enclose this reclaimed land. The 1640 Vermuyden embankment reduced the estuary’s width to approximately 2 miles and this stretch of water was known as Cross Keys Wash or Sutton Wash. Behind this embankment were the villages of Lutton, Long Sutton, Tydd St Mary (further south) and to the east of the river, the Walpoles, including Walpole Cross Keys.

There were ferries at Foul Anchor, east of Tydd St Mary, and another ferry and ford at Walton Dam, further south. But the quickest route was to cross the sands and silt of the Cross Keys Wash. It was a long and dangerous crossing over shifting sands. It was not a pleasant journey.

After crossing the medieval sea bank at Sutton, travellers had negotiate a two mile stretch of common and marsh before arriving at the Wash House (now the Bridge Hotel) for refreshments and perhaps lodgings, while waiting for a guide to take them across to the other side. Slipways enabled travellers, who included drovers with cattle bound for Norwich, horses and passengers of all kinds, to access the river. They were guided up to their middles in water — very uncomfortable and dangerous, and rested at Cross Keys House on the Norfolk bank before continuing their journey east to Kings Lynn and beyond.

Inevitably, there were many accidents. A carriage could suddenly sink in quick sand; horses would be sucked into the soft ground and stick fast. The usual method of freeing them by tramping round and round them a few feet away from them to force them up by counter-pressure — sometimes failed, and the horses were left to drown.

Guides had helped people cross the river at this point for hundreds of years. According to a survey of the manor of Queen Elizabeth I, guides had to pay 12 pence per annum for a licence to guide people across, as it was part of the ‘Queen’s Highway’. There is a tombstone in Long Sutton Churchyard dedicated to William Wigglesworth who, with his horse and long staff guided folk across for 52 years. He died at 85.

The route was sufficiently busy to allow for the building of a bridge over the river at Sutton Wash. The River Welland at Fosdyke had been bridged in 1812-14 and the Ouse at Kings Lynn in 1821. So now the only gap remaining between the north and the east of England was over the River Nene.

In 1826 the Cross Keys Act was passed to build an embankment from the Wash House to the opposite bank in Norfolk with a bridge over the Nene somewhere along its length. The following year another Act was passed allowing a new channel to be cut and land to be reclaimed behind the proposed Cross Keys embankment. In 1829, another Act of Parliament allowed for the erection of two lighthouses, or beacons.

They were to be built at the seaward end of the new cut. They were necessary because the cut entered deep water at a point where the estuary was 3 miles wide. It was believed that shipping could easily miss the entrance to the river, even in daylight. Although called ‘lighthouses’ they were really landmarks because they did not have lights. The one on the west bank was only a short way from dry land, but the east lighthouse was at the end of a 3 mile long embankment that had the Nene on one side and the sands of the old estuary on the other.

[The author gratefully acknowledges the source of much of this information: Sutton Bridge — An Industrial History by Neil R Wright with help from Beryl Jackson: Society for Lincolnshire History and Archaeology; ISBN 978-0-903582-37-7]

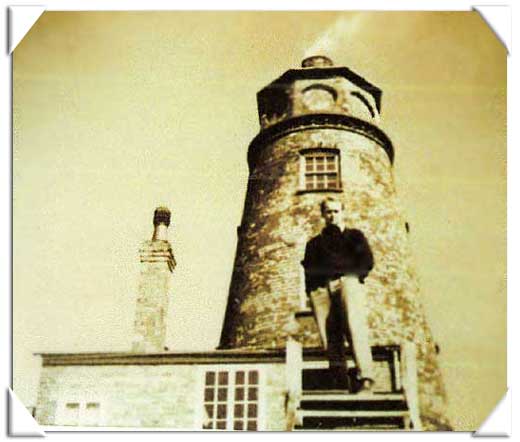

Sir Peter Scott’s lighthouse

Peter Scott’s first encounter with the East Bank Lighthouse was in December 1929. He had commissioned a new punt-boat from a punt builder in Cambridge and with two friends, taking it turns, they brought the boat, named Kazarka, Russian for the Red-breasted goose, to an anchorage on Terrington Marsh (between Sutton Bridge and Kings Lynn). Peter Scott, at this time, was a keen wildfowler and after bagging a Pinkfoot each and three Mallards and two curlews, the two friends set out for the punt. Their intention was to take Kazarka round into the River Nene, four miles direct from where they were by road, but three times further by water at low tide. They intended to leave the punt there over Christmas. They also hoped to stalk more wildfowl.

Finding the tide receding at a rapid rate, they only just had enough time to launch the boat on a narrow trickle of water into a narrow, winding creek. The light was beginning to fade and a strong SSE wind was blowing very hard and it was beginning to drizzle. They were very hungry having had nothing to eat since early morning and Peter Scott later described it as madness that they had even decided to attempt to get into the Nene Channel, which they did not know, and in the dark. They hoped the neap tide would enable them to ‘cuff a good many corners’. The alternative was to turn back and sit and wait in the dark and cold before the tide would flood them back onto the marsh.

As they approached the sea they could it was a big tide and after only just having enough time to get their gun from the front of the punt and turning up the ‘hinged coamings’, the huge waves lifted the boat up and water poured off the decks.

Although they could see a marked wreck on their port side (marked on the chart), they couldn’t see the channel. In fact they were actually sailing away from their destination. However, as the last light faded, they came aground on a lee shore and managed to get the sail down and the oars out. Rowing was no good and the tide was still falling, so they poled onto the sandbar, where they managed to reset the sail. During this time, they had drifted and found themselves literally and figuratively in deep water ten feet and with big waves. Peter Scott wrote later that this was his ‘nastiest moment’. They knew that they had to sail on. The chart they used seemed to bear little relation to where they thought they were and what they could see. By this time they were having to bale out the water that was continually being thrown into the boat.

After what seemed like a long time, and with the boat moving reasonably steadily with less water being taken on board, they decided the time had come to swim. Then, at that moment, they saw land ahead and Peter Scott was able to touch bottom with a ten-foot pole. After going ashore and stowing the mast and sail, they decided to go on rather than leave the boat and walk across the mud. Rowing was useless and so was poling, so they walked and pushed the punt but this proved useless because the punt was still taking water on board. In the end Peter sat in the stern baling out water as fast as it came in, while his friend towed using one of the breeching ropes. They ended up in a dead end with shallow water all around. By this time they could see the glow of light from Kings Lynn, Sutton Bridge and Long Sutton, and the points of lights of cars travelling on the main road about four miles away.

Laying down in the punt to get out of the wind and finding a stale ham sandwich, Peter and his companion drifted off to sleep. They awoke to find the tide beginning to flow, which enabled them to get back into the channel. The tide had subsided and after passing a series of beacons they knew they must be in the right channel. As it straightened they saw the ‘old lighthouses’ and heard geese not far off. They secured the boat and managed to climb up the mud slope and walked along the bank to the lighthouse relieved to be on dry land again. One of the cottagers gave them milk and they set off again to walk the three miles to Sutton Bridge, where they hired a car to take them ten miles to Lynn.

There were many visits to the Terrington and Holbeach Marshes and Peter Scott had been trying for some time to lease the disused lighthouse on the east bank of the Nene. In 1933 he applied for, and was granted, a lease for a rent of £5 per year. The lighthouse was still in use as a ‘hailing post’ for HM Customs and Exercise. There were two customs officers stationed at Sutton Bridge and one of them would arrive half an hour before high water and using a megaphone would hail any ship entering or leaving the river. Half an hour after high water, he would return to Sutton Bridge.

Before this, the lighthouse had been home to a man who worked on the river bank and his family. It had been condemned and unfit for human habitation and had stood vacant for several years until Peter Scott took it over. Peter Scott repointed the brickwork and lined the walls inside to make it reasonably dry. There was a reasonable roadway on the bank serving the farms and cottages but the last half mile to the lighthouse was just the grassy top of the bank. His car frequently slithered and slipped but fortunately never skidded into the river or got stuck in the mud.

The River Nene had a rise and fall of about thirty feet and at low water there was a steep slope of soft mud held together by faggots, which need constant renewing. Nowadays, further reclamations have pushed the salt marsh further north into the Wash. In the 1930s the spring tides surrounded the lighthouse and covered the saltmarsh to the foot of the bank.

Today the inside of the lighthouse is very much as it was when Peter Scott lived there. Its conical shape makes it look more like a windmill than a lighthouse. There are four floors, the bottom one is 16 feet in diameter and above it are three rooms with progressively smaller diameters. The one at the very top is about 6 feet in diameter and there is only just has enough room for a small single bed. It has two small round windows opposite each other and give marvellous views, one up river towards the port (not there in Peter Scott’s time and the power station chimneys); and the other over the sea wall and the mudfalts and saltmarsh beyond. Peter Scoot looked out over the Wash and its sandbanks and saltings.

Peter Scott made his bedroom on the floor below this one. He painted ‘ghostly geese’ on its pale green walls, outlined in white, ‘for ever circling the room’. (Today’s owner sleeps in the extension to the lighthouse.) On the next floor down was a twin-bedded sitting room and the beds hung from stout ropes attached from each corner to the ceiling. When the beds were not in use, a series of blocks and tackles as used to haul the eds up to the ceiling and the room was used as a sitting room. To reach the upper rooms, you had to use ladders through trapdoors. The first floor was and still is, connected with the ground floor by a curved stairway which follows the curve of the wall. The doors are cut into this curve and look most odd when opened! It makes you feel quite giddy! This room was Peter Scott’s living room and studio and was sometimes shared with a Customs Officer at high tide.

A small lean-too had been added to make a kitchen for the previous occupant and Peter Scott added a small bathroom beyond it. Outside, steps lead down to a basement. This space was occupied by a gentleman of the road called Charlie, a big friendly red-haired man who collected cockles and samphire in the summer and worked as a handyman in the winter.

The East Lighthouse was Peter Scott’s home until the beginning of the Second World War. During those five years he added a flat-roofed studio that overlooked the marsh. He also added a larger bedroom and a bunk room that connected with the garage and boathouse that he had constructed at first. He also made a new front entrance that led from a gravel driveway into a small hall. This last addition, he said, made it a ‘proper home’.

His initial intention had been to use the lighthouse as a temporary base for wildfowling weekends but he soon began to see it as a permanent home. Before he could do this he had to pipe fresh water to it and this could only be done by making a connection to the main across the river near the West Lighthouse. It was easier than expected: he simply crossed the river in a boat with a load of pipes, connecting them together and allowing them to sag down on the bed of the river. The supply was only secure as long as no ship came up river stern first, dragging an anchor. His system worked for the next five years.

His other main intention was to keep waterfowl on the marsh around the lighthouse. He made enclosures using a fifty-foot roll of six-foot wire netting and some metal stakes bought from the hardware shop in Sutton Bridge. The wire fence was erected around small pool on the salt marsh close to the lighthouse. It was about 20 yards long and five yards wide. Fifteen geese were introduced to this enclose. However, he soon realised that something larger would be need and would mean more planning.